Here are some tips from a full-time fence builder on how to string steel so it lasts long enough for the next generation of cowboys to cuss it, too.

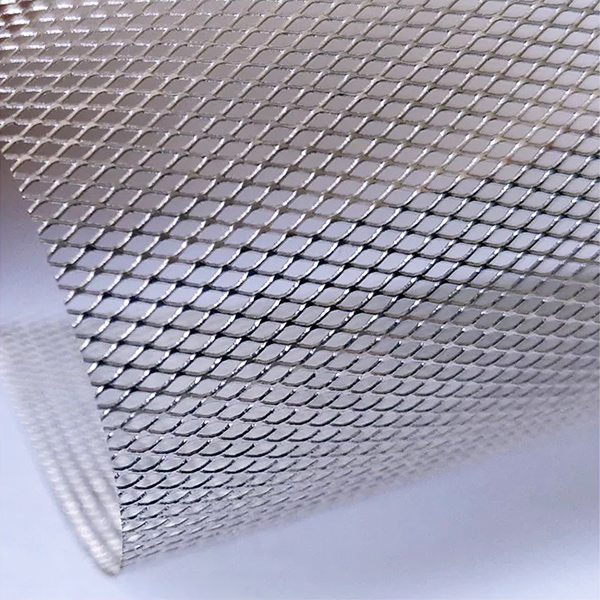

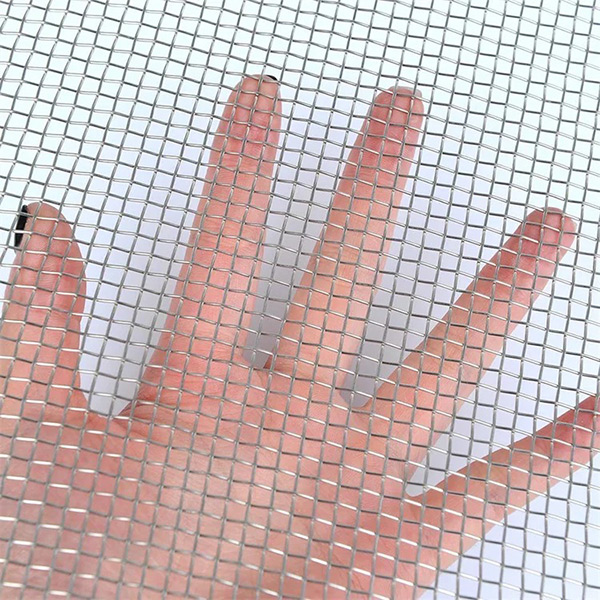

Take a look back into the history of ranching in the U.S. and what do you guess that historians peg as an early game-changer? Stainless Steel Wire Mesh Standard Sizes

You got it. Barbed wire.

While many attributes of that time-honored and cowboy-cussed string of steel have changed, its original purpose is as necessary today as it was when the first patent for barbed wire was issued in 1867.

Here are some tips from a full-time fence builder on how to string steel so it lasts long enough for the next generation of cowboys to cuss it, too.

The key to a good fence is good braces. Michael Thomas, Thomas and Son Custom Fencing, Baker, Idaho (son of the author), says a good barbed wire fence can be built in nearly any terrain, as long as you match bracing for the terrain.

“In flat country, you can go a lot farther between braces, but if geography is variable you need more braces, shortening the distance. We try not to stretch wire through low places or over high places without bracing,” he says.

If it’s steep, Thomas puts a brace in the low spots even if it’s just a simple H-brace to stabilize the fence, hold it down in that area and give something to pull the wire to.

The distance between braces will vary depending on a lot of factors, including terrain, animal pressure and how many strands the fence will have. But as a general rule, shorter is better; and Thomas says a quarter-mile between braces, even on level ground, is the absolute maximum.

Related: 7 common cattle fencing mistakes

For corners, Thomas says any good brace will work. However, he prefers a double H-brace on each leg of the corner over an H and a diagonal. “You are depending so much on that pole. If it fails, the brace fails. The double H-brace is actually stronger, and those shorter brace poles are less apt to get knocked out.”

It is important to tie off the wire at a brace, securing it solidly to the brace posts rather than just stapling the wire — even on long runs. “When we rebuild fences for people and have to take apart and remove the old fence, we often find the wires were not secure. Even though the original builder went to the trouble to put in braces at appropriate locations, they didn’t pull to the brace; they just ran the wire by and stapled it to the posts,” he says.

This defeats the purpose of the brace because there is always some give, even if the posts are set right. “You need a solid attachment to the brace posts; otherwise you are putting all your faith in just the staples — and they don’t last,” says Thomas.

In low spots like a gully, a good brace will generally hold the fence down if posts are well-set. “We don’t use anything less than 6-inch-diameter posts for most braces in that kind of country. Smaller posts don’t have as much anchor quality,” he says.

Related: 6 Tips for proper electric fence grounding

“In gullies that have washed to bedrock, your chances of setting a post securely are limited. Sometimes you can set two posts — one on either side of the exposed rock. In extreme cases, where we can’t set posts, we gather rocks to make a rock basket as an anchor for the fence in that low spot.”

“You want it tight and straight between posts, with no droops, but not so tight that it vibrates when you hit it, like when sinking staples into the brace posts,” he says. If you’re playing a tune with your hammer, the fence is tight enough that it might break.

The longer the run, the harder it is to tell how tight to pull it — and experience is the best teacher. It’s helpful to have another person or two along the line to check as you pull it. If you’re working by yourself, put on your hiking boots.

“That’s really the only way to know if it’s tight enough along the line, but not too tight. New barbed wire has some stretch in it, and you want to take out most of that stretch — but not all of it — or it will break when you hit it with the hammer.”

Distance between posts and braces depends on terrain and soil type. In flat country with good ground to hold posts, you can go farther between posts, and often use a lot of steel T-posts, which are cheaper than wood, between braces.

“Depending on the pressure from livestock and wildlife, we may add wood posts fairly often to help support the line of steel posts,” Thomas says. “We usually go with wood about every fourth or fifth post, to add stability and visibility.”

A long run of T-posts without wood posts interspersed is more likely to be laid over by animals going over it or pushing against it. The wood post every 50 or 60 feet gives metal posts more help, so you won’t find the fence bent over or down on the ground, says Thomas.

“Anywhere the ground is wet in various seasons, from irrigation, rain or thaw, T-posts alone are pretty weak if cattle press on the fence. They don’t have enough diameter to give enough resistance in wet ground. If you think there will be much pressure, you need wood posts more frequently,” he says.

Post height will depend on the height of your fence and whether you are using three, four or five wires or more. There is no reason to pay for a foot or more of extra post height above your top wire, he says.

“Calculate the depth the posts need to be in the ground, the height of the top wire, and give yourself a couple inches in case you need to fudge over uneven ground — and that’s how tall your posts should be. On metal, just make sure you have one or two nobs above your top wire to secure it, so it won’t pop off the top,” he says.

How many wires and the spacing between wires can vary depending on how large the pasture is, how much pressure the fence might have, and whether or not wildlife will be going through or over it.

“In a pasture with lush feed on either side, with cattle trying to reach through the fence, I recommend five strands, minimum. The fence also needs stays to help keep the wire spacing, so cattle can’t stick their heads through,” says Thomas.

If there is a lot of wildlife traffic, some people use just four wires, to make it easier for wildlife to go over or through without tearing down the fence. “You could use three barbed wires, and a smooth or barbless wire for the bottom strand. I don’t like this for cattle [they tend to reach under or through it more], but you can get away with it if you make sure you space the wires correctly.”

In those situations, wire stays are a necessity, so cattle can’t push up that barbless bottom wire. “If they get their head under or through it, then their neck follows, and soon they are on their knees reaching, putting more stretching force on the fence, and the wires won’t stay tight. The four-strand fence with barbless bottom wire works if it’s well-braced, with a wire stay between posts — and no more than 12 feet between posts,” he explains.

Thomas prefers wire stays over wood. “Though some people are opposed to wire stays [because they get bent or may be difficult to put in], they last longer. It’s hard to staple wood stays onto the fence, and they may come off. A wire stay is permanent, whereas wood shrinks over time and the staples come out,” he says.

“If a wire stay gets bent, you can straighten it or cut it out and put a new one in. It’s durable for the life of the fence, whereas wood stays look good the first year and don’t last.”

Thomas says people think wood stays are cheaper, and sometimes they are initially, but they take more time to install and more maintenance. If you calculate the value of the stay based on efficiency of installation and life expectancy, wire stays are better, he says.

The key to wire stays is how you install them. “Some people don’t know how to put them in and think it’s too difficult. The old, cheap, galvanized stays can be a challenge, but a trick that makes them easier to install is to undo the bundle, spread them out over the tailgate of your pickup or any flat place, and spray them with a coating of WD-40. Then they go onto the wires very easily,” Thomas says.

“More important is how you install them. As you spin them down over the wires — pushing them down and threading them through the fence — don’t let them grab the next wire where they would naturally take hold of it, or they will bind. Take them a half-turn past, or sometimes a full revolution past, that next wire, so they can connect with it in a neutral-pressure situation. Then they’ll spin onto each wire, all the way to the bottom, without binding.”

Most people get in a hurry and let the stay grab that next wire as they are shoving it down. “By the time you get to the third or fourth wire, you can barely force those stays to go any farther. If you avoid letting them grab where they first make contact, however, and back off to release the pressure — so there is no pressure when they connect with that next wire — you can spin them in without problems,” he explains.

“If you get hold of that next wire and the stay is going in hard, just back it out and let it run another revolution or half-revolution before you let it grab the wire. This saves hours of misery!”

Smith Thomas is a rancher and writer from Salmon, Idaho.

The dollars and sense of sustainability

Enter a zip code to see the weather conditions for a different location.

P5 Ranch in Kansas changes hands

Winter weather challenges for bulls can affect breeding season

Spring weather update: A first look at how planting season is shaping up

Perforated Stainless Steel Screen Copyright © 2024 All rights reserved. Informa Markets, a trading division of Informa PLC.